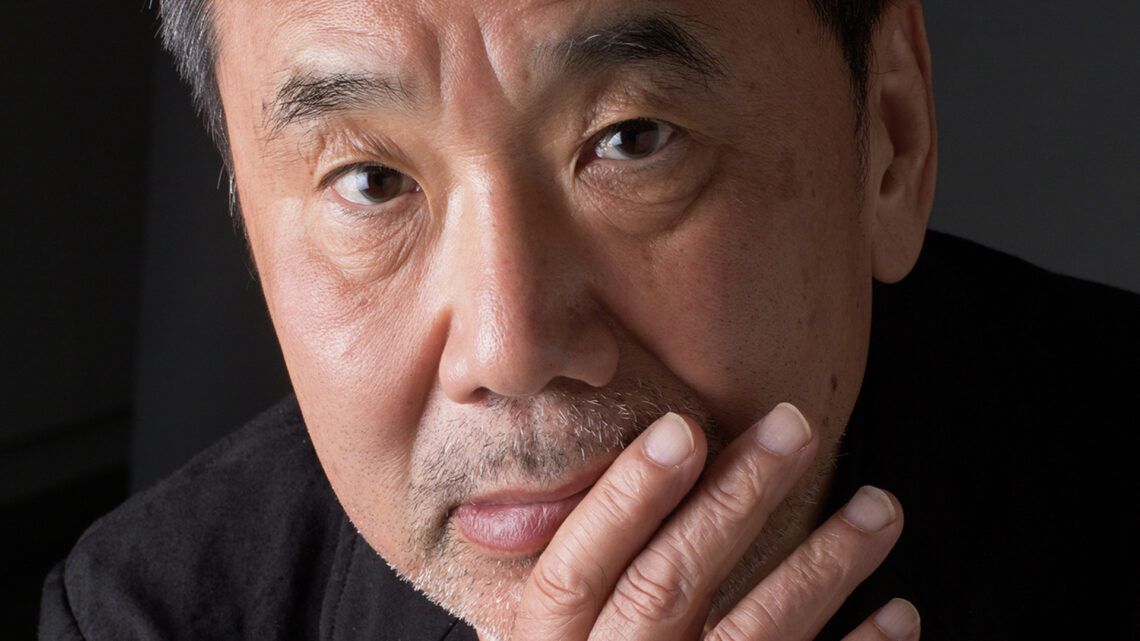

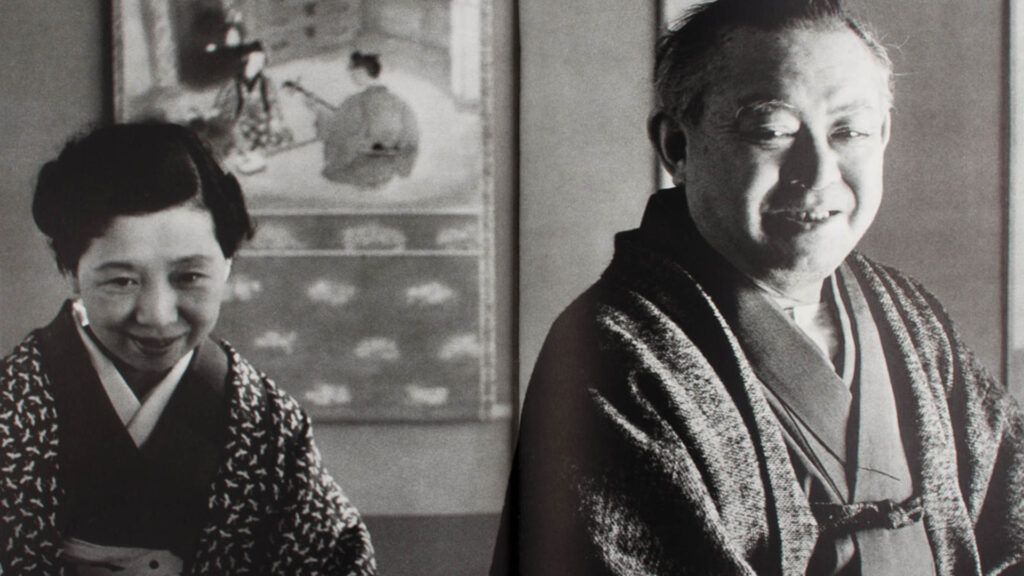

Tanizaki Jun’ichiro is considered one of the most important Japanese writers of the 20th century and, alongside Kawabata Yasunari and Mishima Yukio, stands as a pillar of modern Japanese literature. His works, characterized by a unique blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics and Western modernism, have received acclaim not only in Japan but also internationally. Born in 1886 and deceased in 1965, the author created a literary universe characterized by the tension between tradition and modernity, by the depths of human sensuality, and by the search for beauty.

Tanizaki’s work spans over five decades of literary creation, during which he continually evolved while always maintaining his distinctive style. His novels, short stories, and essays not only reflect the dramatic changes Japan experienced in the first half of the 20th century, but also offer timeless insights into human nature and the complexity of interpersonal relationships.

Tanizaki’s distinctiveness lies in his ability to explore the psychological depths of his characters while simultaneously creating prose of exceptional aesthetic beauty. His works are characterized by a subtle eroticism, a fascination with the bizarre and grotesque, and a deep connection with Japanese culture and its traditions. However, he was never a backward-looking traditionalist, but rather an artist who sought to meet the challenges of modernity with great literary refinement.

Early Years and Formation (1886-1910)

Tanizaki Jun’ichiro was born on July 24, 1886, in Nihonbashi, a traditional merchant district in Tokyo. His family belonged to the merchant class, which was of great importance for his later literary development. His father, Tanizaki Kuraemon, ran a business selling rice and other staple foods, while his mother, Seki, came from a family of artisans. This connection between commercial activity and artistic craftsmanship would shape Tanizaki’s understanding of both the practical and aesthetic aspects of life.

Childhood in Nihonbashi offered the young Tanizaki a direct insight into traditional Meiji-era Tokyo. The district was a vibrant center of commerce and culture, where ancient traditions mingled with the new influences of Western civilization. This early experience of cultural hybridity would become a central theme in his later work. The streets of Nihonbashi, the shops, the theaters, and the people who lived and worked there provided a rich source for his literary imagination.

Tanizaki’s family was not wealthy, but they placed great value on education. The boy demonstrated an exceptional aptitude for language and literature at an early age. Already in elementary school, he stood out for his ability to read and write complex Chinese characters. This early mastery of classical Chinese script, an essential component of traditional Japanese education, gave him profound access to East Asian literary tradition.

Tanizaki spent his middle school years at Tokyo Prefectural First Middle School, a prestigious institution that has produced many important figures in modern Japan. It was here that he first encountered Western literature in depth. He read works by Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire, and Oscar Wilde, which made a lasting impression on him. Poe’s tales of the bizarre and grotesque, as well as Wilde’s aestheticism, particularly resonated with his own artistic sensibility.

During his school years, Tanizaki also began his own literary explorations. He wrote poems and short prose pieces that already hinted at some of the themes that would shape his later work: a fascination with the beautiful and the forbidden, the tension between tradition and modernity, and a subtle yet pervasive eroticism. His teachers recognized his talent and encouraged him to pursue his literary ambitions.

A formative experience of his youth was the death of his father in 1899, when Tanizaki was thirteen years old. This loss had not only emotional but also practical consequences for the family. The financial situation worsened, and Tanizaki was forced to assume responsibility at an early age. This experience of loss and responsibility deepened his understanding of the fragility of human relationships and the impermanence of life—themes that recur repeatedly in his work.

After graduating from middle school in 1905, Tanizaki enrolled at the prestigious Imperial University of Tokyo, where he studied Japanese literature. The university was a center of intellectual ferment at the time, where traditional Japanese scholarship mingled with Western ideas. Tanizaki studied under some of the most prominent literary scholars of his time and deepened his understanding of both classical Japanese and modern Western literature.

During his university years, Tanizaki’s literary activity intensified. He participated in the founding of the literary magazine “Shinshicho” (New Currents of Thought) in 1907, which became an important forum for young, experimental writers. This magazine strove to modernize Japanese literature and open it up to new, Western influences without completely rejecting native traditions.

Tanizaki’s university years were also a time of intense personal development. He experimented with various literary styles and themes, searching for his own artistic voice. He was strongly influenced by the Decadent movement in European literature, which celebrated the beautiful, sensual, and transgressive. At the same time, he studied classical Japanese literature intensively, particularly works of the Heian period such as “Genji Monogatari” (The Tale of Genji).

A key turning point in Tanizaki’s early development was his encounter with the work of Nagai Kafu, an established writer known for his depictions of urban life and pleasure districts. Kafu’s ability to capture the atmosphere of modern Tokyo while maintaining a nostalgic yearning for the past inspired Tanizaki and helped him develop his own literary approach.

During his university years, Tanizaki also began to explore the complex relationships between the sexes, which would later become a central theme in his work. His early stories already demonstrated his fascination with strong, dominant women and weaker, submissive men—a reversal of traditional gender roles that was both shocking and fascinating.

However, his time at university ended abruptly in 1910 when Tanizaki failed to graduate. The exact reasons for this are not entirely clear, but it seems that a combination of financial difficulties, family obligations, and a burning desire to devote himself entirely to literature led to this decision. This step was risky, as he forwent the security of a university career to pursue the uncertain path of a freelance writer.

Abandoning his studies marked the end of Tanizaki’s youth and the beginning of his career as a professional writer. At 24, he was at the beginning of a literary path that would make him one of the most important authors of Japanese modernism. The influences of his early years—the combination of traditional and modern culture, his early encounter with Western literature, his experience of loss and responsibility, and his intense preoccupation with questions of aesthetics and human nature—would permeate his entire work.

The Literary Breakthrough (1910-1920)

The year 1910 marked not only the beginning of Tanizaki’s professional writing career, but also a time of profound social change in Japan. The Meiji era was nearing its end, and the country was undergoing a rapid modernization process that encompassed all areas of social life. In this context of transformation, Tanizaki found his literary voice and established himself as one of the leading representatives of the new generation of Japanese writers.

His literary breakthrough came as early as 1910 with the publication of the short story “Shisei” (The Tattooing) in the magazine “Shinshicho.” This story, about a tattoo artist who takes sadistic pleasure in inflicting and observing pain, immediately established Tanizaki’s reputation as an author unafraid to explore the darker aspects of human nature. The story was characterized by an aestheticized depiction of violence and eroticism that both shocked and fascinated.

“Shisei” already showcased many of the signature elements of Tanizaki’s style: the psychological complexity of the characters, the combination of beauty and cruelty, and the subtle eroticism that pervades his works. The story follows a master tattoo artist who selects a young woman to tattoo the image of a spider on her back. During the painful process, a sadistic nature awakens within the woman, simultaneously attracting and terrifying the tattoo artist. This reversal of power relations and the portrayal of women as both victims and perpetrators became a recurring motif in Tanizaki’s work.

The publication of “Shisei” brought Tanizaki immediate recognition in literary circles, but also criticism from more conservative voices who considered his depiction of sexuality and violence too explicit. This controversial reaction only strengthened Tanizaki’s determination to explore the boundaries of socially acceptable and to portray the complex and often contradictory aspects of the human experience in his works.

In the following years, Tanizaki further developed his signature style and published a number of short stories that cemented his position as an innovative and provocative author. Stories such as “Kirin” (1910), “Shonen” (The Boy, 1911), and “Akuma” (The Demon, 1912) explored themes such as homosexual relationships, sexual obsession, and the intersection of normality and perversion. These works were characterized by a decadent aesthetic that combined Western influences with traditional Japanese elements.

“Kirin,” for example, tells the story of a young man seduced by an older, sophisticated gentleman. The story not only explores homosexual relationships at a time when this was largely taboo in Japanese society, but also the dynamics of power and submission in interpersonal relationships. Tanizaki’s treatment of this subject was both insightful and analytical, without judgment or moralizing.

“Shonen,” on the other hand, deals with a young person’s emerging sexuality and their confusion in the face of their own feelings and desires. The story demonstrates Tanizaki’s ability to portray the psychological complexities of adolescence, capturing both the innocence and burgeoning sensuality of his characters. This sensitive portrayal of adolescent sexuality was remarkably progressive for the time.

During this early phase of his career, Tanizaki was heavily influenced by Western literary movements, particularly Aestheticism and Symbolism. He admired authors such as Oscar Wilde, Charles Baudelaire, and Edgar Allan Poe, and their influences are clearly evident in his early works. At the same time, however, he strove to develop a distinctly Japanese literary voice that combined Western techniques with native traditions.

An important aspect of Tanizaki’s early work was his use of the Japanese language. He experimented with different stylistic levels and registers, from highly formal classical language to colloquial everyday speech. This linguistic diversity enabled him to portray different social classes and psychological states with great precision. His prose was characterized by a rhythmic quality that emphasized both the musicality of the Japanese language and the psychological nuances of his characters.

In addition to his writing, Tanizaki was also active as a translator during this period. He translated works by Western authors into Japanese, thereby contributing to cultural understanding. This translation work deepened his understanding of various literary traditions and influenced his own writing. His translations of Edgar Allan Poe, in particular, were highly regarded and helped to popularize this author in Japan.

In 1915, Tanizaki married Ishikawa Chiyoko, a union that had both personal and literary significance. Chiyoko came from an educated family and was herself interested in literature. The marriage brought Tanizaki emotional stability and inspired him to write a series of works that explored the complexities of marital relationships. At the same time, this relationship was not without tension, as Tanizaki’s intense preoccupation with literature and his unconventional views on sexuality and relationships sometimes led to conflict.

The period surrounding World War I was a period of economic prosperity and cultural openness for Japan. Tanizaki benefited from this cultural climate and established himself as one of the leading representatives of literary modernism in Japan. His works were regularly published in major literary journals, and he began to develop a loyal readership that appreciated his innovative treatment of sexuality, psychology, and aesthetics.

Towards the end of the decade, Tanizaki began writing longer works that allowed him to develop his themes and characters in greater detail. In 1918, he published the novel “Otsuya Goroshi” (The Murder of Otsuya), a complex tale of jealousy, betrayal, and revenge. This work demonstrated his increasing mastery in constructing longer narratives and his ability to maintain psychological tension over extended periods.

“Otsuya Goroshi” tells the story of a man who discovers that his wife is having an affair and his increasingly obsessive reaction to this discovery. The novel explores the dark aspects of marital relationships and shows how love can turn into hatred and destruction.

Tanizaki’s portrayal of his characters’ psychological development is both insightful and unsparing, and he doesn’t shy away from depicting the self-destructive aspects of human passion.

During this period, Tanizaki also developed his characteristic interest in portraying strong, dominant women. Many of his female characters are complex and multifaceted, neither pure heroines nor simple villains, but psychologically realistic figures with their own motivations and desires. This portrayal was remarkable for the time, as it contradicted traditional notions of female subservience and passivity.

The 1910s were also a time of intense literary friendships for Tanizaki. He maintained close relationships with other important writers of his generation, including Akutagawa Ryunosuke and Sato Haruo. These friendships were both personally enriching and literary stimulating, as the authors inspired and critiqued each other. The intellectual exchange with like-minded people helped Tanizaki sharpen and further develop his own literary ideas.

Towards the end of the 1910s, however, Tanizaki’s literary orientation began to change. While his early works were strongly influenced by Western influences, he increasingly became interested in traditional Japanese culture and aesthetics. This development was partly a reaction to the changing cultural situation in Japan, where, after the initial enthusiasm for all things Western, a return to native values began.

The end of the 1910s thus marked a turning point in Tanizaki’s career. He had established himself as a major author and developed a distinctive literary voice, but he was also at the beginning of a new phase in his artistic development, one that would lead him to a deeper engagement with Japanese tradition. The foundations he had laid in this first decade of his career—the psychological complexity, aesthetic refinement, and fearless exploration of human passions—would, however, form the foundation for all his subsequent work.

The Middle Period (1920-1935)

The 1920s and early 1930s marked one of the most productive and artistically rich phases in Tanizaki’s literary career. This period was characterized by an increasing maturity of his style, a deepening of his thematic interests, and a notable turn toward traditional Japanese values ??and aesthetics. At the same time, it was a time of personal upheaval and social change, all of which were reflected in his literary output.

A pivotal event at the beginning of this period was the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, which devastated Tokyo and the surrounding areas. This natural event not only had a physical impact on Japan but also led to cultural and psychological change. Many intellectuals and artists, including Tanizaki, began to question Japan’s rapid modernization and Westernization and instead turned to traditional values ??and native culture.

After the earthquake, Tanizaki left Tokyo and moved to the Kansai region, first to Osaka and later to Kyoto. This geographical relocation had a profound impact on his literary output. Kansai, with its ancient cities of Kyoto, Osaka, and Nara, was the heart of traditional Japanese culture. Here, Tanizaki was able to experience the remnants of the old world that had largely disappeared in Tokyo due to modernization. The traditional architecture, ancient customs, classical cuisine, and refined social mores of the Kansai region exerted a strong fascination on him.

This cultural shift was directly reflected in his literary works. While his early stories were heavily influenced by Western influences and often set in a modern, Westernized setting, his works of the 1920s increasingly began to explore traditional Japanese themes and settings. This development, however, was not a simple return to tradition, but a complex synthesis of traditional and modern elements.

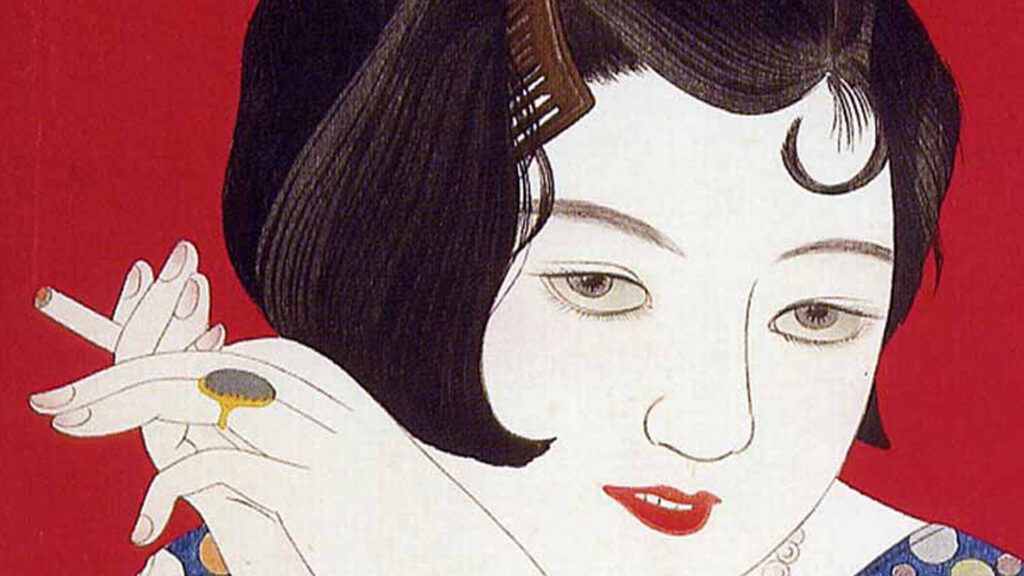

In 1924, Tanizaki published “Chijin no Ai” (Love of a Fool), a novel that is one of his best-known and most controversial works. This novel tells the story of Kawai Joji, an older man who is obsessed with a younger woman named Naomi. For Joji, Naomi embodies the ideal of Western beauty and modernity—she is tall, has Western features, and loves Western fashion and culture. Joji’s obsession with Naomi leads to his complete submission to her will and ultimately to his social and financial ruin.

“Chijin no Ai” was notable for its unsparing portrayal of male weakness and female power. The novel reverses traditional gender roles and depicts a woman using her sexuality as a weapon to gain power over men. At the same time, the work is a critique of the uncritical adoption of Western values ??and beauty ideals. Naomi’s “Western” beauty proves to be superficial and destructive, while Joji’s fascination with her can be interpreted as a symbol of Japan’s blind adoration of the West.

The novel was a huge success with audiences but also sparked fierce controversy. Conservative critics accused Tanizaki of undermining Japanese morals and disseminating pornographic content. More progressive voices, however, praised the work as a brilliant psychological study and an important contribution to modern Japanese literature. This controversial reaction only enhanced Tanizaki’s reputation as a provocative and innovative author.

In the following years, Tanizaki continued his exploration of gender relations with a series of works that demonstrated his increasing psychological sophistication. “Manji” (1928-1930), originally serialized in a magazine, is a complex work about a lesbian love triangle between two women and the husband of one of them. The novel explores themes such as sexual identity, jealousy, and the destructive power of passion with a candor that was extraordinary for the time.

“Manji” is distinguished by its innovative narrative technique. The novel is told from the perspective of one of the female protagonists, who recounts her story to a psychoanalyst. This frame narrative allows Tanizaki to explore the psychological complexities of his characters with great depth while maintaining a certain emotional distance from the often disturbing events of the plot.

The portrayal of the lesbian relationship in “Manji” was remarkably progressive for the 1920s. Tanizaki treats the relationship between the two women not as an abnormality or perversion, but as a form of love that possesses its own intensity and beauty. At the same time, he also shows the destructive aspects of this passion and how it drags all involved into the abyss. This balanced portrayal demonstrates Tanizaki’s ability to explore complex human relationships without moral judgment.

During this period, Tanizaki also began to engage more intensively with classical Japanese literature. He studied the great works of the Heian period, such as The Tale of Genji and The Makura no Soshi (Pillow Book), and was inspired by their refined aesthetics and psychological subtlety. These classical influences began to be reflected in his own works, both in their thematic orientation and stylistic approach.

In 1929, Tanizaki began work on a modern translation of The Tale of Genji into contemporary Japanese. This monumental project, which he ultimately revised three times, was not only a literary achievement but also an act of cultural preservation. The Tale of Genji, although recognized as the greatest work of classical Japanese literature, had become difficult for modern readers to understand due to its archaic language. Tanizaki’s translation made this masterpiece accessible to a new generation of readers.

The work on the translation of The Tale of Genji had a profound impact on Tanizaki’s own writing. He became increasingly fascinated by the subtle psychology and refined aesthetics of Heian literature. These influences were evident in his own works of the 1930s, which exhibited a new depth and elegance. His prose became more nuanced and lyrical, while his characterizations became even more psychologically complex.

In 1933, Tanizaki published one of his most important essays, “In’ei Raisan” (In Praise of the Shadow). This essay is both an aesthetic meditation and a cultural critique. Tanizaki argues that traditional Japanese aesthetics are based on the beauty of shadows, nuances, and subtle nuances, in contrast to the Western preference for bright light and clear contours. He laments the loss of this traditional aesthetic in the modern world and advocates a return to native values.

“In’ei Raisan” is more than just an aesthetic treatise; it is a philosophical reflection on the differences between Eastern and Western culture. Tanizaki uses concrete examples from architecture, cuisine, theater, and other areas of daily life to illustrate his arguments. He describes how traditional Japanese spaces deliberately use subdued lighting to create an atmosphere of mystery and contemplation, while Western spaces are brightly lit and conceal nothing.

The essay had a tremendous impact on cultural thought in Japan and beyond. It inspired architects, designers, and other artists to incorporate traditional Japanese aesthetics into their work. For Tanizaki himself, the essay was an important step in his development toward a more mature, tradition-informed aesthetic that would shape his later masterpieces.

During this middle creative period, Tanizaki also experienced significant personal changes. In 1930, he divorced his first wife, Chiyoko, and married Furukawa Tomiko in 1931. This new marriage brought him emotional fulfillment and inspired some of his finest works on marital love and the complexities of long-term relationships. Tomiko came from a traditional Kansai family and, for Tanizaki, embodied many of the qualities he admired in the traditional Japanese woman: grace, refinement, and a subtle strength.

The new marriage also influenced Tanizaki’s literary interests. He began to delve more deeply into the domestic aspects of traditional Japanese culture—the cuisine, clothing, social mores, and the intimate rituals of family life. These themes found their way into his works, lending them a new warmth and authenticity.

In 1932, Tanizaki published “Yoshinokuzu” (Yoshino-Kudzu), a novella that perfectly embodies his new appreciation for traditional Japanese culture. Set in the historical region of Yoshino, the story follows a man attempting to trace the legacy of a legendary beauty from the past. The novella is laced with references to classical Japanese literature and history, demonstrating Tanizaki’s ability to blend historical and contemporary elements into a coherent artistic vision.

“Yoshinokuzu” is distinguished by its lyrical quality and its evocative depiction of the Japanese landscape. Tanizaki uses the natural beauty of the Yoshino region as a metaphor for the transient beauty of traditional Japanese culture. The story is both a tribute to this culture and a meditation on the inevitability of change and loss.

During this period, Tanizaki also experimented with various literary forms and techniques. He wrote plays, essays, and poems, continually expanding his artistic repertoire. His interest in traditional Japanese theater, particularly kabuki and bunraku, influenced his prose, lending it a theatrical quality that was particularly evident in his dialogue and characterizations.

In 1935, Tanizaki began work on what many consider his masterpiece: “Sasameyuki” (Snow on the Bamboo Leaves, often known in English as “The Makioka Sisters”). Although the novel was not published in its entirety until 1948, the first chapters were written in the mid-1930s. This monumental novel, which follows the life of a traditional merchant family in Osaka, represents the culmination of Tanizaki’s engagement with traditional Japanese culture and his ability to portray complex familial relationships.

The middle period of his work was also marked by Tanizaki’s increasing international fame. His works began to be translated into English and other languages, and he received recognition as one of the most important contemporary Japanese authors. This international attention heightened his awareness of the uniqueness of Japanese culture and motivated him to emphasize these distinctive features even more clearly in his works.

At the same time, this period was marked by growing political tensions in Japan. The rise of militarism and increasing nationalism created a difficult environment for writers who had explored Western ideas or who critically questioned traditional Japanese values. Tanizaki skillfully navigated these dangerous waters by increasingly focusing on purely literary and aesthetic themes and avoiding political statements.

His turn to traditional Japanese culture during this period can be understood partly as a reaction to these political pressures, but it was also a natural evolution of his artistic vision. Tanizaki recognized that the modernization and Westernization of Japan was irreversible, and he saw his role as a writer as preserving and documenting the beauty and complexity of the vanishing traditional culture.

The middle creative period ended with Tanizaki at the height of his artistic power. He had transformed his early fascination with Western decadence and modernity into a mature, nuanced engagement with Japanese tradition. His works from this period demonstrate a remarkable synthesis of psychological depth, aesthetic refinement, and cultural authenticity. The foundations were laid for the masterpieces of his later years, which would definitively establish him as one of the greatest writers of Japanese modernism.

Personal Life and Interpersonal Relationships

Tanizaki’s personal life was as complex and fascinating as his literary works. His relationships with women, his family ties, and his friendships not only shaped his personal development but also continuously influenced his literary output. The boundaries between life and art were often fluid for Tanizaki, and many of his works contain autobiographical elements, which were, however, so artfully transformed that they express universal human truths.

His first marriage to Ishikawa Chiyoko in 1915 was initially marked by great passion. Chiyoko was an educated woman from a wealthy family and brought Tanizaki not only emotional fulfillment but also financial stability. The early years of their marriage were characterized by shared literary interests and mutual inspiration. Chiyoko often served as the first reader of Tanizaki’s manuscripts and provided him with valuable feedback on his works.

However, Tanizaki’s intense personality and obsessive preoccupation with literature were not always easy for his spouses to bear. His tendency to blur the lines between fiction and reality and his fascination with unconventional relationships led to tensions in the marriage. Chiyoko sometimes felt like an object of his artistic observation rather than an equal partner.

The relationship was further complicated by Tanizaki’s friendship with fellow writer Sato Haruo. What began as a literary friendship developed into an unusual love triangle when Sato fell in love with Chiyoko, and Tanizaki not only tolerated this development but even seemed to encourage it. This situation reflected themes that appeared in many of his literary works: the complexity of human relationships, the power of passion, and the willingness to break social conventions.

In 1930, this complicated relationship dynamic ultimately led to the divorce of Chiyoko, who married Sato Haruo. Tanizaki arranged this divorce with a serenity that astonished his friends and family. For him, this was not just the end of a marriage, but also a literary experiment, a way to explore the boundaries of interpersonal relationships. This experience later influenced several of his works, particularly his depictions of complex love triangles.

The following year, Tanizaki married Furukawa Tomiko, a woman who matched his ideal of traditional Japanese beauty. Tomiko came from a wealthy merchant family in Osaka and embodied many of the qualities Tanizaki admired in traditional Japanese culture: elegance, refinement, and a quiet strength. This marriage was significantly more stable than his first and lasted until his death.

Tomiko understood and accepted Tanizaki’s artistic temperament and supported him in his literary work. She was not only a loving wife but also a muse, inspiring some of his finest works on marital love and the beauty of the mature woman. Their marriage was characterized by mutual respect and a deep emotional connection, which is reflected in the warmth and authenticity of his later works.

Tanizaki’s relationship with his daughters also shaped his life and work. He had two daughters from his first marriage, Ayuko and Tatsuko, and his role as a father brought a new dimension to his understanding of human relationships. His love for his daughters was profound and complex, marked by tenderness but also by a certain concern for their future in a rapidly changing world.

His relationship with his daughters inspired him to create several works that explored generational differences and the challenges of fatherhood. He was a caring but also demanding father who placed great value on his daughters’ education and cultural development. At the same time, he was aware that they were growing up in a world very different from that of his own childhood.

Tanizaki’s friendships with other writers were also of great importance to his personal and literary life. His relationship with Akutagawa Ryunosuke, one of Japan’s most important short story writers, was particularly important. Although the two authors pursued different literary approaches—Akutagawa was known for his intellectual, often pessimistic stories, while Tanizaki was more interested in sensual and psychological themes—they developed a deep mutual appreciation.

His friendship with Akutagawa was characterized by intense literary discussions and mutual criticism. Both authors benefited from this intellectual exchange, and their correspondence offers fascinating insights into the Japanese literary scene in the 1920s. Akutagawa’s suicide in 1927 was a severe blow for Tanizaki and led him to reflect more deeply on the role of the writer in society and the burdens of the artistic life.

Another important aspect of Tanizaki’s personal life was his relationship with his mother. Seki Tanizaki was a strong, traditional woman who had a profound influence on her son. Her stories about old Tokyo and traditional Japanese customs shaped Tanizaki’s idea of ??ideal Japanese womanhood. Even after his marriage, he remained deeply attached to his mother, and her death in 1917 was a traumatic event for him.

His relationship with his mother also influenced his literary portrayals of women. Many of his female characters display a mixture of strength and grace, which he associated with his mother. At the same time, his portrayal of mother-son relationships was often complex and ambivalent, marked by love but also by a certain anxiety.

Tanizaki’s interest in traditional Japanese arts was also closely linked to his personal life. He was a passionate lover of kabuki theater and developed friendships with many prominent actors. His appreciation for the sophistication and artistry of kabuki influenced his prose, giving it a theatrical quality. He particularly admired the art of onnagata, male actors playing female roles, and their ability to perfect femininity as an art form.

His interest in traditional Japanese cuisine was another important aspect of his personal life. Tanizaki was a gourmet who placed great value on the aesthetic and cultural aspects of food. He viewed traditional Japanese cuisine as a form of art that engages all the senses and creates a deep connection to cultural identity. This appreciation for culinary art flowed into many of his works and contributed to their sensual quality.

Tanizaki’s relationship with his physical health also shaped his life and work. He suffered from various ailments, including stomach problems and neuralgia, which often caused him great pain. These physical ailments heightened his awareness of the fragility of the human body and the transience of life. At the same time, they led to an even greater appreciation for sensual pleasures and physical beauty.

His attitude toward money and material possessions was characteristic of his personality. Although he achieved success through his writing, he tended to live lavishly and spend his money on luxury goods, travel, and cultural experiences. This attitude reflected his belief that life should be enjoyed to the fullest and his rejection of puritan values.

Tanizaki’s personal relationships were often characterized by a certain theatricality. He loved to stage scenes and create emotional dramas, which he then incorporated into his literary works. This tendency toward dramatic art made him a fascinating, yet sometimes difficult, person to deal with. His friends and family had to learn to cope with his intense personality and his need to create life as a kind of work of art.

The complexity of his personal relationships was reflected in the psychological depth of his literary characters. Tanizaki understood human nature in all its contradictions and was able to integrate these insights into his works. His own experiences with love, loss, passion, and disappointment gave his stories an authenticity and emotional resonance that transcends cultural and temporal boundaries.

The War Years and Their Impact (1935-1945)

The years of World War II represented one of the most difficult and complex periods of Tanizaki’s life and literary career. As Japan became increasingly entangled in militarism and eventually entered the devastating Pacific War, Tanizaki faced the challenge of surviving as an artist and intellectual in an era of extreme nationalism and censorship. His response to these challenges reveals both his human weaknesses and his remarkable ability to rise above the turmoil of the times through art.

As early as the mid-1930s, the Japanese government began to exert increased pressure on writers and other intellectuals to support national goals. Freedom of expression was increasingly restricted, and many authors were forced to either deny their beliefs or remain silent. Tanizaki, whose earlier works often displayed Western influences and questioned traditional Japanese values, found himself in a particularly precarious position.

His response to this situation was characteristic of his complex personality. Rather than openly opposing the regime, which would likely have led to his arrest or worse, he chose the path of internal exile. He largely withdrew from public literary life and focused on projects considered politically unobjectionable. This strategy allowed him to maintain his artistic integrity while avoiding martyrdom.

A central project of this period was his work on translating The Tale of Genji into modern Japanese. This monumental task, which he had begun in the early 1930s, offered him a refuge from the political turmoil of the time. Engaging with this masterpiece of classical Japanese literature allowed him to immerse himself in a world of aesthetic sophistication and psychological complexity, far removed from the crude propaganda and militarism of the present.

Translating The Tale of Genji, however, was more than just an escape from reality. It was also an act of cultural resistance, an assertion of the continuity and value of Japanese civilization beyond current political aberrations. By making this great work of the past accessible to contemporary readers, Tanizaki preserved an understanding of Japanese culture that was more nuanced and humanistic than the government’s nationalist propaganda.

In 1937, the authorities began to exert direct pressure on Tanizaki. His novel “Manji” was criticized by censors for its depiction of homosexual relationships and its content, which was generally considered immoral. The magazine that had serialized the novel was ordered to cease publication. Similar problems arose with other of his works, which were considered too Western or too decadent.

This censorship was a traumatic experience for Tanizaki. As an artist who had dedicated his entire life to the free exploration of human experience, the restriction of his expressive freedom was a form of spiritual mutilation. He reacted with a mixture of anger, despair, and a defiant determination to find a way to continue his art despite the restrictions.

During this difficult time, Tanizaki found comfort and inspiration in his relationship with his second wife, Tomiko. Their marriage, which had taken place in 1931, proved to be an anchor of stability in a time of chaos. Tomiko understood and supported his desire to focus on non-political literary projects and helped him create an environment in which he could work despite external turmoil.

In 1943, Tanizaki began work on what many consider his masterpiece: “Sasameyuki” (The Makioka Sisters). This monumental novel, depicting the life of a traditional merchant family in Osaka in the years before the war, was in many ways an act of remembrance and resistance. At a time when Japan defined itself as a militaristic power, Tanizaki evoked a more complex and humane vision of Japanese society.

“Sasameyuki” was also a risky undertaking, as the novel depicted a world condemned by wartime propagandists as decadent and unpatriotic. The Makioka family, with its focus on personal relationships, aesthetic pleasures, and traditional mores, stood in sharp contrast to the spartan ideals the regime sought to promote. Tanizaki was aware of this risk, but he was determined to preserve and document his vision of Japanese culture.

Working on “Sasameyuki” was both a form of therapy and protest for Tanizaki. By creating a world of beauty and humanity, he resisted the barbarism and dehumanization of war. The novel became a refuge for him, a place he could retreat to when reality became too overwhelming.

The war years also brought personal losses for Tanizaki. Many of his friends and colleagues were drafted or died in the war. The literary community that had been so important to his intellectual life was decimated. These losses reinforced his sense of isolation and his belief that art was one of the few constants in a chaotic world.

Despite the difficulties, Tanizaki refused to write propaganda or to put his art in the service of the war effort. This stance cost him material benefits and exposed him to criticism, but it allowed him to maintain his artistic integrity. His refusal to compromise was a silent but powerful act of resistance against the tyranny of conformism.

The later years of the war, as Japan increasingly suffered from bombing and defeat became inevitable, brought new challenges. Tanizaki and his family had to relocate several times to escape the bombing raids. Their homes were damaged or destroyed, and precious manuscripts and books were lost. These material losses were painful, but they also reinforced Tanizaki’s conviction in the transience of all earthly things.

In the final months of the war, as Japan lay in ruins and society was in a state of collapse, Tanizaki was already beginning to think about the future. He realized that the war represented not only a political and military defeat, but also an opportunity for spiritual and cultural renewal. This insight would shape his postwar work and help him find a way out of despair.

The surrender of Japan in August 1945 brought Tanizaki a mixture of relief and uncertainty. On the one hand, he was happy that the madness of the war was finally over and that he could write freely again. On the other hand, he was aware that Japan would undergo a complete transformation and that the world he had documented in his works was finally gone.

The war years had changed Tanizaki as a person and as an artist. The experience of oppression, loss, and uncertainty had taught him to appreciate the power of art to preserve human values ??in times of crisis. His ability to adhere to his artistic vision despite adverse circumstances demonstrated his strength as a writer and as a person. These experiences would form the basis for his most significant work and help him achieve a new artistic maturity in the postwar period.

Postwar Period and Late Masterpieces (1945-1965)

Jun’ichiro Tanizaki is one of the most important Japanese writers of the 20th century and left a lasting mark on Japanese literature through his unique narrative style and his profound exploration of traditional and modern elements of Japanese society. While his early works already received international acclaim, Tanizaki reached the pinnacle of his literary mastery in the postwar period and his later creative years between 1945 and 1965. These two decades mark a period of extraordinary creative productivity, during which the author wrote some of his most famous and influential novels.

The end of World War II in August 1945 marked a decisive turning point not only for Japan but also for Tanizaki personally. At the age of 59, the writer faced the challenge of continuing his literary work in a completely different social and political context. The American occupation, the introduction of democratic principles, and the far-reaching social reforms of the postwar period created new conditions for literary creation.

Tanizaki responded to these changes not with a radical reorientation of his writing, but rather with a deepening and refinement of the themes and techniques that had already characterized his earlier work. The postwar period offered him the opportunity to write without the constraints of wartime censorship and to devote himself entirely to the themes that most interested him: the complexity of human relationships, the tensions between tradition and modernity, and the subtle power dynamics within Japanese society.

Tanizaki’s writing style underwent a remarkable evolution, characterized by increasing sophistication and subtlety. While his earlier works were often characterized by dramatic twists and explicit depictions, in his later years he developed a more restrained, yet all the more effective, narrative style.

A characteristic feature of his later works is the masterful use of suggestion and the unspoken. Tanizaki was unparalleled in his ability to create tension by omitting important information and compelling readers to read between the lines. This technique, known in Japanese aesthetics as “ma”—the meaningful empty space—became a hallmark of his mature prose.

The narrative perspective in Tanizaki’s later works is often complex and multi-layered. He experimented with different narrators and focalizations to explore the psychological depth of his characters. He used the first-person narrative particularly skillfully to provide intimate insights into the minds of his protagonists, while simultaneously addressing the unreliability of human perception and memory.

Tanizaki’s language during this period is characterized by an elegant blend of classical and modern elements. His translation work on The Last Genji had sharpened his sense of the beauty of classical Japanese while also mastering the expressive possibilities of modern colloquial language. This synthesis enabled him to create texts that were accessible to both educated readers and a wider audience.

The thematic focuses of Tanizaki’s postwar work reflect both his personal obsessions and the larger societal transformations in Japan. A central theme is the transience and loss of traditional values ??in a rapidly modernizing society. Tanizaki was a keen observer of cultural change and documented the transition from a feudal to a democratic society in his novels.

The complexity of family relationships is another focus of his later works. Tanizaki was particularly interested in the power relations within families and the way social changes influence these traditional structures. His depictions of marriage, parent-child relationships, and sibling dynamics are characterized by psychological depth and a nuanced understanding of human motivations.

Sexuality and eroticism, which had already played an important role in his earlier works, are treated with greater subtlety and psychological complexity in his later novels. Tanizaki was less concerned with explicit depictions than with exploring the emotional and psychological dimensions of sexual relationships. He showed how sexual dynamics are intertwined with power, control, and identity.

The exploration of age and the transience of life became an increasingly important theme in Tanizaki’s later works. As an aging man, he reflected on the changes in the body, the loss of youth, and the approach of death. However, he treated these themes not with melancholy, but with a peculiar blend of acceptance and rebellious humor.

Sasameyuki (Snow on the Bamboo Leaves) – The Postwar Masterpiece

Tanizaki’s novel “Sasameyuki,” written between 1943 and 1948 and published in its entirety in 1949, is considered his masterpiece and one of the most important Japanese novels of the 20th century. The work tells the story of the four sisters of the Makioka family during the late 1930s and documents the decline of the traditional Japanese upper class in meticulous detail.

The novel’s genesis is remarkable. Tanizaki began work during the war, but was stopped by censors because his portrayal of middle-class life was considered unpatriotic. He was only able to complete the work after the war ended. This interruption proved artistically productive, as it gave Tanizaki the opportunity to rethink and refine his original conception.

The novel is structured around the efforts to find a suitable husband for the third sister, Yukiko. This seemingly simple plot, however, becomes the starting point for a comprehensive social study. Tanizaki uses the ritual aspects of matchmaking to explore the complex social codes and hierarchies of Japanese society.

The four sisters—Tsuruko, Sachiko, Yukiko, and Taeko—represent different responses to the social changes of their time. Tsuruko, the eldest, embodies the preservation of traditional values ??and structures. Sachiko, around whom the narrative primarily revolves, stands between tradition and modernity. Yukiko, the unfortunate protagonist of the matchmaking attempts, represents the victims of societal expectations. Taeko, the youngest, breaks most radically with convention and expresses her individuality.

Tanizaki’s portrayal of the sisters is characterized by remarkable psychological depth. He shows not only their outward actions, but also their inner conflicts, their unspoken desires, and their fears. His depiction of the subtle power games and alliances between the sisters, which are played out without explicit confrontation, is particularly masterful.

The novel’s language is characterized by an elegant simplicity that corresponds to the complexity of the social relationships depicted. Tanizaki uses a narrative technique that can be described as “objective exposition,” in which the narrator describes events in a seemingly neutral manner while simultaneously offering a subtle critique of social conditions through the selection and arrangement of details.

A distinctive feature of the novel is its depiction of seasonal cycles and their significance for the characters’ lives. Tanizaki uses the seasons not only as a temporal orientation but also as symbolic elements that reflect the characters’ emotional states and developments. This technique, deeply rooted in Japanese literary tradition, gives the novel a poetic dimension.

The sociocritical aspects of “Sasameyuki” are subtle but powerful. Tanizaki shows how the rigid social structures of traditional Japanese society hamper individual development and force women, in particular, into restrictive roles. At the same time, he documents with ethnographic precision the rituals, customs, and values ??of a social class that is on the verge of disappearing.

The novel’s international success, which has been translated into numerous languages, established Tanizaki’s worldwide reputation. Edward Seidensticker’s English translation made the work accessible to a broad Western audience and contributed significantly to promoting understanding of the complexity of Japanese society.

Kagi (The Key) – Psychological Mastery

In 1956, Tanizaki published the novel “Kagi” (The Key), a work that demonstrates his mastery of psychological characterization and his ability to portray complex sexual dynamics. The novel tells the story of an aging professor and his wife, whose marriage takes on new dimensions through a series of experiments with sexuality and voyeurism.

The novel’s structure is particularly innovative. Tanizaki tells the story through two parallel diaries—one belonging to the professor and one belonging to his wife. This technique allows him to illuminate the same events from two different perspectives and demonstrate the differences in perception and interpretation of the two protagonists.

The professor, the first-person narrator of the first diary, is a middle-aged man concerned about his declining sexual potency. In his diary, which he supposedly hides from his wife, he documents his attempts to revitalize the erotic life of his marriage. His entries reveal a complex psychology characterized by insecurity, voyeurism, and an obsessive desire for control.

His wife’s diary, which she also keeps secretly, offers a completely different perspective on the same events. Her entries reveal that she knows more about her husband’s machinations than he suspects and that she is pursuing her own agenda. This dual perspective creates a complex narrative structure in which the truth only becomes apparent through the combination of both viewpoints.

Tanizaki’s treatment of sexuality in “Kagi” is both explicit and psychologically nuanced. He shows how sexual relationships are intertwined with power, control, and self-image. The professor uses sexuality as a means to assert his dominance, while his wife wields it as a weapon in a subtle psychological struggle.

The introduction of the young student Kimura as the woman’s lover further complicates the dynamic. Through this character, Tanizaki addresses generational differences and the threat that younger men can pose to aging husbands. However, Kimura is not just a simple antagonist; he himself becomes a pawn in the complex psychological game between the spouses.

A particularly fascinating aspect of the novel is the way Tanizaki blurs the lines between reality and fantasy. The diary entries often leave it unclear whether the events described actually occurred or whether they reflect the writers’ wishful thinking or fears. This ambiguity contributes to the psychological depth of the work and makes it a study in the unreliability of human perception.

The novel’s language is characteristic of Tanizaki’s late style. It is precise and controlled, yet at the same time characterized by an underlying intensity. Particularly remarkable is his ability to describe intimate and sexual scenes without slipping into pornography. Instead, he focuses on the emotional and psychological dimensions of sexuality.

“Kagi” was controversial upon its publication, as its frank treatment of sexuality was unusual for the time. At the same time, the novel was praised by critics for its psychological complexity and innovative narrative technique. The work established Tanizaki as one of the leading psychologists of modern Japanese literature.

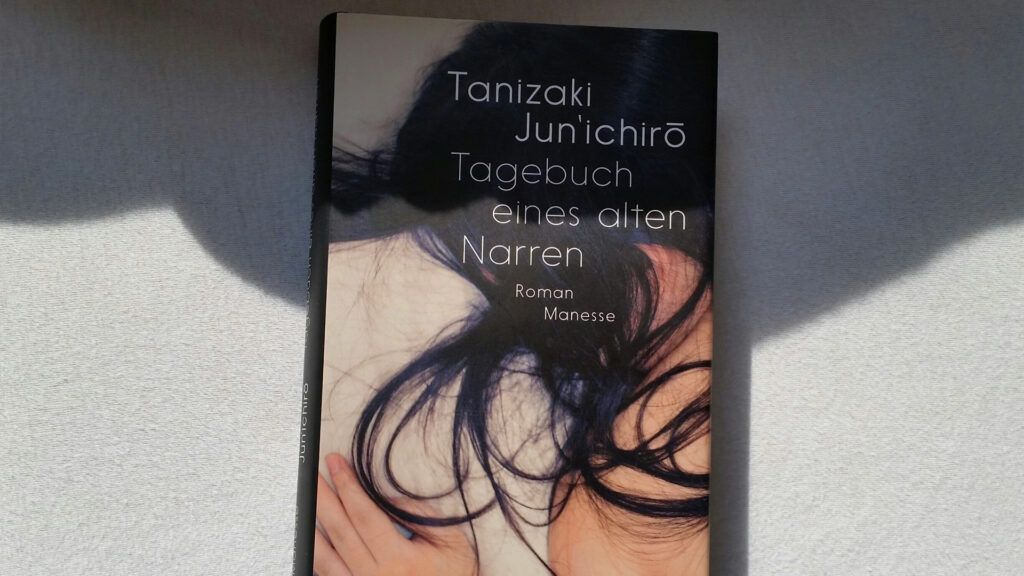

Futen Rojin Nikki (The Diary of a Mad Old Man)

In 1961, Tanizaki published his last major masterpiece, “Futen Rojin Nikki” (The Diary of a Mad Old Man). The novel, written in diary form, tells the story of 77-year-old Utsugi Tokusuke, who falls in love with his family’s young daughter-in-law and allows his final years to be dominated by this obsessive passion.

The work is both a haunting portrait of aging and a meditation on desire, transience, and the power of beauty. Tanizaki, who was himself in his 70s when he wrote the novel, brought a personal authenticity to his portrayal of the aging protagonist that makes the work particularly moving.

The protagonist, Utsugi, is a retired businessman who compensates for his physical weakness and health problems with an intense erotic obsession. His passion for Satsuko, his son’s wife, becomes the dominant theme of his life. This passion, however, is not only sexual but also aesthetic—he is fascinated by her beauty and youthfulness.

The diary format allows Tanizaki to delve deeply into his protagonist’s psyche. Utsugi’s entries reveal not only his obsessive thoughts, but also his self-doubt, his shame, and his desperate fear of death. The intimate perspective makes the reader a confidant in the old man’s secret thoughts and plans.

Satsuko, the object of Utsugi’s obsession, is a complex character who transcends the role of a passive beauty. She is aware of the power of her beauty and skillfully uses it to manipulate her father-in-law and gain material advantages. Her relationship with Utsugi is a complex game of seduction and exploitation, in which both parties are both perpetrators and victims.

The portrayal of the Utsugi family offers Tanizaki the opportunity to address the changes in postwar Japanese society. The traditional family structure is destabilized by the patriarch’s obsession and the machinations of the daughter-in-law. The younger generation, represented by Utsugi’s son, is helplessly caught between the fronts.

A particularly fascinating aspect of the novel is the way Tanizaki depicts the physical aspects of aging. Utsugi’s health problems—his heart problems, his declining strength, his difficulty walking—are described with brutal candor. At the same time, the author shows how these physical limitations intensify the protagonist’s psychological obsessions.

The novel’s erotic elements are characteristic of Tanizaki’s late style. They are explicit enough to convey the intensity of Utsugi’s obsession, but at the same time, they possess a poetic quality that elevates them above mere pornography. Particularly noteworthy are the scenes in which Utsugi worships Satsuko’s feet—a motif that reflects Tanizaki’s own predilections while simultaneously becoming a symbol of the degradation and ecstasy of passion.

The novel’s language is characterized by a remarkable directness and intimacy. Tanizaki eschews literary embellishments and focuses on the immediate rendering of his protagonist’s thoughts and feelings. This simplicity makes the work’s emotional impact all the more powerful.

The novel’s ending, which coincides with Utsugi’s death, is marked by a peculiar reconciliation. The old man dies not in despair, but in a kind of erotic ecstasy that transforms his obsession into a transcendent experience. This portrayal of death as fulfillment rather than defeat is characteristic of Tanizaki’s philosophy of life.

Other Important Works of the Late Period

In addition to these three major masterpieces, Tanizaki created several other important works in the postwar period that complete his literary legacy. These texts demonstrate the versatility of his talent and his ability to master various literary forms.

“Yume no Ukihashi” (The Floating Bridge of Dreams), a novel published in 1959, deals with the complex relationship between a young man and his stepmother. The work is heavily autobiographical and reflects Tanizaki’s own psychological obsessions. The narrative is structured around the protagonist’s memories of his childhood and adolescence, blurring the boundaries between reality and fantasy, between memory and wishful thinking.

The novel “Neko to Shozo to Futari no Onna” (A Cat and Two Women), begun in 1936 but not published in its final version until 1957, is a humorous reflection on a man’s love for his cat and the complications that arise when his ex-wife wants the cat back. The work demonstrates Tanizaki’s talent for comedy and his powers of observation for the absurdities of human relationships.

“Shisei” (The Tattoo), although originally written in 1910, was reworked by Tanizaki in the 1950s and demonstrates his continued fascination with themes of beauty, power, and sexual dominance. The story of a tattoo artist who transforms a young girl into a femme fatale through his artwork is characteristic of Tanizaki’s interest in the transformative power of art.

The essay collection “In’ei Raisan” (In Praise of the Shadow), written in 1933 but republished in the postwar period and becoming internationally known, is Tanizaki’s most important contribution to aesthetic theory. In this essay, he develops his philosophy of Japanese aesthetics, which considers shadow, darkness, and transience as essential elements of beauty. These ideas influenced not only his own work but also the understanding of Japanese culture in the West.

Tanizaki’s Influence on Japanese Literature

Tanizaki’s influence on Japanese literature can hardly be overestimated. His postwar works set new standards for psychological complexity and narrative sophistication in Japanese prose. His ability to explore his characters’ inner worlds and portray complex familial and sexual relationships, in particular, influenced an entire generation of younger writers.

Tanizaki’s treatment of female characters was revolutionary for his time. Unlike most of his male contemporaries, he created women who functioned not merely as objects of male desire, but as complex individuals with their own motivations and strategies. His female characters are often stronger and more manipulative than the male protagonists, representing a subtle critique of the power relations of patriarchal society.

The stylistic innovations of his later works, particularly the use of multiple narrative perspectives and the technique of foreshadowing, were adopted by many subsequent authors. His ability to create suspense by omitting key information became a defining characteristic of modern Japanese literature.

Tanizaki’s exploration of Japan’s modernization and the loss of traditional values ??resonated strongly with the experiences of the postwar generation. His works offered a nuanced perspective on social change that was neither nostalgically backward-looking nor uncritically progressive.

International Reception and Translations

The international recognition of Tanizaki’s work began in the 1950s with the first translations of his novels into English. Edward Seidensticker’s translation of “Sasameyuki” in 1957, in particular, introduced Tanizaki to a broad Western audience. These and other translations contributed significantly to deepening Western understanding of Japanese literature.

Tanizaki’s reception in the West was characterized by a fascination with his exotic portrayal of Japanese culture and, at the same time, by a recognition of the universal validity of his psychological insights. Critics particularly praised his ability to address culture-specific themes in a way that made them understandable and relevant to readers from other cultures.

In Europe, Tanizaki’s works received considerable attention, particularly in France and Germany. French structuralists appreciated the complex narrative structure of his novels, while German critics compared his psychological depth to the tradition of European social novels.

The translation of “Kagi” and “Futen Rojin Nikki” in the 1960s reinforced Tanizaki’s reputation as a master of psychological analysis. These works were often compared to the novels of Marcel Proust and other European modernists, placing Tanizaki within the canon of world literature.

Tanizaki’s Literary Philosophy

Tanizaki’s writing in the postwar period was shaped by a specific literary philosophy that had developed over decades. At the heart of this philosophy was the conviction that literature should reflect the complexity of human experience in all its contradictions and ambiguities.

A central aspect of his philosophy was the rejection of moral clarity. Tanizaki’s characters are neither clearly good nor clearly evil, but rather operate in the gray areas of human motivation. This ambiguity reflects his conviction that reality is too complex to be divided into simple moral categories.

His aesthetic philosophy, most clearly articulated in “In Praise of Shadows,” emphasizes the beauty of the imperfect and the transient. This attitude influenced not only the thematic focus of his works but also his narrative techniques. The deliberate use of ellipses, allusions, and unresolved tensions reflects his conviction that true art conceals more than it reveals.

In Tanizaki’s later works, the subjective perception of time and the power of memory play a central role. His protagonists are often elderly people living in a rapidly changing world and attempting to preserve their identity by reconstructing their past. This theme lends his works a melancholic depth that transcends the concrete actions.

The way Tanizaki depicts memory is remarkably nuanced. He shows how memories are distorted by current needs and desires, how selective they are, and how they can provide both comfort and torment. This psychological precision makes his characters particularly believable and human.

Although Tanizaki was never considered a political writer in the strict sense, his later works contain a subtle but penetrating critique of the social conditions of his time. His portrayal of postwar society demonstrates the disorientation and loss of values ??that accompanied rapid modernization.

He was particularly critical of the dissolution of traditional family structures and the associated erosion of social bonds. His novels document the transition from a collectivist to an individualistic society and the associated psychological costs.

Tanizaki’s Legacy and Aftermath

When Tanizaki died on July 30, 1965, at the age of 79, he left behind a literary legacy that has had a lasting impact on Japanese culture. His later masterpieces from 1945 to 1965 represent the culmination of a remarkable literary career and are among the most important works of modern world literature. The lasting impact of his works is evident not only in the continuous reprinting and retranslation of his books, but also in their influence on subsequent generations of writers. Authors such as Mishima Yukio, Oe Kenzaburo, and many others have explicitly referenced Tanizaki’s work and further developed his techniques.

His treatment of themes such as age, sexuality, and family relationships was groundbreaking for the development of modern Japanese literature. The openness with which he addressed taboo topics opened new possibilities for literary exploration and contributed to the liberalization of cultural discourse.

Conclusion: A Master of Psychological Analysis

The twenty years between 1945 and 1965 mark Tanizaki Jun’ichiro’s artistic achievement. During this time, he created works of extraordinary psychological depth and aesthetic sophistication that masterfully capture both the complexity of human nature and the tensions of changing Japanese society.

His ability to explore the inner world of his characters with such precision and empathy makes him one of the great psychologists of world literature. His works offer not only insights into Japanese culture but also universal truths about the human condition.

Tanizaki’s late masterpieces remain relevant because they address questions that every generation must answer anew: How do we relate to tradition and modernity? How do we cope with aging and transience? How do we navigate the complexities of interpersonal relationships? His nuanced answers to these questions make his works timeless classics.

The international recognition Tanizaki received in his later years was not only an appreciation of his individual talent, but also a recognition of the universality of great literature. His works demonstrate that culturally specific experiences, when treated with sufficient depth and artistry, can become universal statements about the human experience.

Today, more than half a century after his death, Tanizaki’s late works remain living texts that fascinate and inspire new generations of readers. They stand as a monument to the power of literature to explore and illuminate the deepest secrets of the human heart.