Bizen pottery, one of Japan’s oldest and most traditional ceramic art forms, captivates with its raw beauty, natural essence, and profound connection to Japanese culture. With origins dating back over 1,000 years, it has inspired artisans and art enthusiasts worldwide throughout the centuries. This article delves deeply into the history, evolution, and unique characteristics of Bizen pottery.

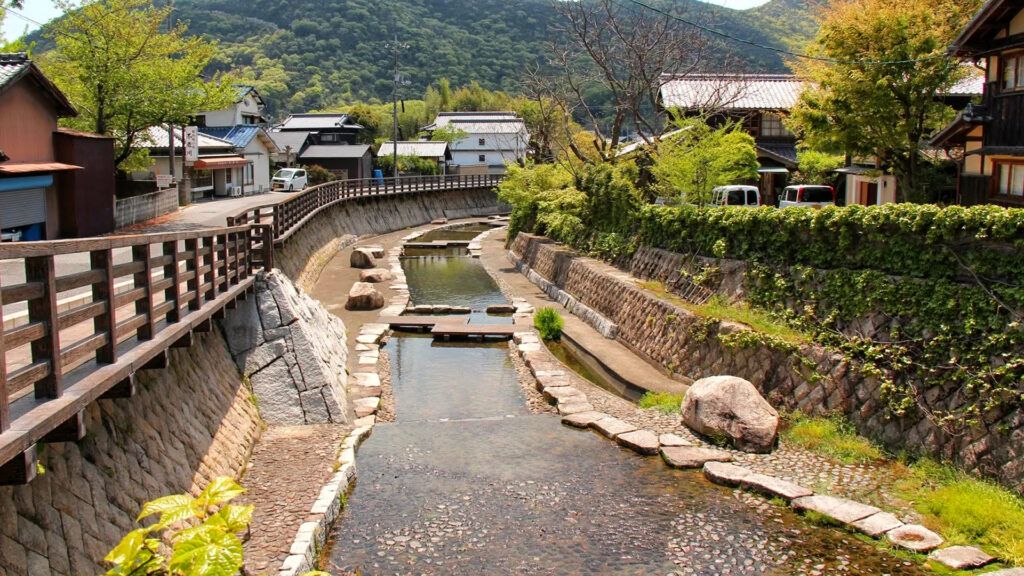

Bizen pottery originates from the Bizen province, now part of Okayama Prefecture in Japan. Archaeological evidence suggests its history dates back to the 6th century when simple pottery was crafted in open pit fires. The region’s abundant clay deposits provided ideal conditions for the development of this art form.

By the 12th century, during the Kamakura period, Bizen pottery underwent a significant transformation. The introduction of anagama wood-fired kilns, which allowed for higher temperatures and longer firing times, gave rise to a new aesthetic. The clay from the region, renowned for its fire-resistant quality and high iron content, became the foundation for the distinctive appearance of Bizen pottery.

The Bizen region offered exceptional resources for pottery production. Its soil, rich in iron-bearing clay, was known for its strength and fire-resistant properties. This unique clay played a critical role in creating the durability and characteristic reddish-brown color of Bizen pottery.

Additionally, the dense forests of the area provided abundant wood for kiln firing. The development of the anagama wood-fired kiln, introduced in Japan towards the end of the 6th century, revolutionized pottery production. These kilns enabled prolonged firing at consistently high temperatures, making the pottery surfaces more resilient and enhancing their color intensity.

In its early stages, Bizen pottery focused on the production of practical vessels used in agriculture, as well as for storing and transporting food and liquids. Large storage jars, water jugs, and bowls were particularly popular, emphasizing the functional and utilitarian nature of early pottery production.

However, during the Heian period (794–1185), the role of pottery began to shift. Influenced by Buddhist temples and the rising wealth of the aristocracy, demand grew for more aesthetically refined objects. Potters began to transition from creating purely functional items to crafting pieces of artistic value.

The introduction of the anagama kiln marked a turning point. This long, tunnel-like kiln allowed multiple pieces of pottery to be fired simultaneously, with the placement of items in the kiln having a profound effect on the final outcome. Pieces closer to the fire source developed unique textures and color variations due to direct exposure to ash and flames. These spontaneous effects enhanced the individuality of Bizen pottery, setting the stage for its later recognition as an art form.

Even in its early years, Bizen pottery formed a deep connection with Japanese aesthetics and philosophy. Its simplicity and natural beauty aligned perfectly with the emerging Wabi-Sabi philosophy, which celebrates imperfection and transience as elements of beauty. This connection would play a central role in later centuries, particularly during the tea ceremony tradition.

Like many other Japanese ceramic styles, Bizen pottery was influenced by Chinese and Korean techniques. During the Nara period (710–794), traders and craftsmen from mainland Asia introduced advanced firing methods and design concepts to Japan. These influences, combined with the local resources and craftsmanship of Bizen potters, resulted in a distinctive style.

By the 12th century, Bizen pottery began gaining recognition beyond its regional borders. Merchants and nobles appreciated the durability and unique appearance of the pottery, making it increasingly sought after as a trade good. Support from local feudal lords, who recognized the economic importance of the pottery industry, also contributed to its growth. The origins of Bizen pottery are deeply intertwined with nature, culture, and technology. These early developments laid the foundation for an art form that continues to be admired to this day.

Special features of Bizen ceramics

Bizen ceramics are characterized by their simplicity and the absence of glazes. Instead, the unique textures and colors are created by the influence of fire and ash during the firing process. Each creation is unique because the random patterns cannot be reproduced.

It embodies a natural beauty that is created by deliberately avoiding glazes, sophisticated firing techniques and the influence of fire during the manufacturing process. The distinctive features of Bizen ceramics can be described in various aspects:

Unglazed surface – The raw beauty of the clay

An outstanding feature of Bizen ceramics is that they are made without glazes. Unlike other ceramic styles where glazes provide shine or color, Bizen ceramics show the raw, unvarnished texture and color of the clay.

Naturalness: The iron-rich clay from the Bizen region gives the ceramics a warm red to dark brown base color.

Surface structure: The unglazed surface preserves the natural texture of the clay and makes each piece uniquely tactile.

This lack of glazes reflects the philosophy of Bizen ceramics: a deep appreciation of natural materials and processes that is in line with the wabi-sabi aesthetic.

Unique color and texture variations through the firing process

The magic of Bizen ceramics is created in the anagama kiln, where fire, ash and temperature leave their distinctive marks on the ceramics. The art of Bizen ceramics is based on controlling and using these unpredictable effects.

Hidasuki (fire cord pattern)

- This pattern is created when ceramics are wrapped in rice straw before firing. During firing, the straw burns and the ash leaves reddish or orange stripes. This technique is one of the most famous and appreciated features of Bizen pottery.

Goma (sesame effect)

- Goma is created when ash particles melt on the surface of the clay, forming small, shiny, glassy dots. This effect is reminiscent of scattered sesame seeds and gives the pieces a fascinating mix of shine and texture.

Sangiri

- Sangiri is a color gradient caused by varying levels of oxygen in the kiln. Parts of the pottery piece that are more exposed to the flame turn dark gray to black, while other areas remain in warm red tones.

Yohen (kiln changes)

- Yohen describes unpredictable changes caused by the heat of the fire and the movement of the ash in the kiln. These effects are often referred to as the “gift of fire” and are a symbol of the symbiosis between man and nature.

Robustness and functionality

Bizen pottery is not only beautiful, but also extremely durable. The iron-rich clay is fired at extremely high temperatures of 1,200 to 1,400 °C, giving the ceramics exceptional hardness and water resistance. This robustness makes them ideal for everyday use, whether in the form of tea bowls, water jugs or flower pots.

Minimalist shapes

The designs of Bizen ceramics are deliberately kept simple to focus on the natural beauty of the clay and the unpredictable effects of the fire. They are often traditional shapes that have been used for centuries, such as:

- Simple tea bowls with gently rounded edges

- Jugs and vases with clean lines

- Small, asymmetrical bowls that highlight the potter’s craftsmanship

Timelessness through aging

Another notable feature of Bizen ceramics is their ability to age over time and become even more beautiful in the process. The surface takes on subtle changes with use, especially in pieces used for tea or flowers. This patina, created by touch, water and time, is highly prized by collectors and connoisseurs.

The combination of chance and control

The success of a Bizen piece depends heavily on its placement in the anagama kiln and the potter’s ability to control the firing process, although this is heavily influenced by chance. Ceramicists devote years of experience to learn the ideal firing point and proper positioning.

Bizen pottery is an unparalleled craft based on centuries-old techniques that celebrate the raw beauty of nature. Its distinctive features – from the unglazed surface to the fascinating patterns and textures left by the fire – make it a unique expression of Japanese aesthetics and craftsmanship.

Cultural significance and use

Bizen pottery had not only aesthetic but also practical uses. It reached its peak during the Muromachi and Momoyama periods, playing a central role in the tea ceremony. The rough surface and natural appearance of Bizen wares were in perfect harmony with the wabi-sabi aesthetic, which seeks beauty in imperfection.

Bizen pottery has been deeply embedded in Japanese culture and tradition for centuries. Its cultural significance goes far beyond its aesthetic and craft qualities, reflecting the values, customs and spiritual beliefs of Japan. From the tea ceremony to spiritual practice, Bizen pottery has occupied a unique position that makes it a symbol of the connection between art and everyday life.

The Japanese tea ceremony, known as chanoyu, is one of Japan’s most significant cultural traditions. It is closely linked to the Wabi-Sabi philosophy, which sees beauty in simplicity, naturalness and transience. Bizen ceramics, with their rough, unglazed surface and the random patterns of the fire, embody this philosophy perfectly.

The rough and asymmetrical shapes of Bizen tea bowls harmonize with the Wabi-Sabi ideal. Each bowl is considered a unique work of art that reflects the power of nature and the craftsmanship of the potter. Bizen tea bowls are thus not only decorative but also functional. Their thick walls hold the warmth of the tea, while their texture makes it pleasant to the touch.

The frequent use of Bizen ceramics in the tea ceremony symbolizes the harmony between man and nature. The raw clay and the random patterns of the fire are reminiscent of the transience and beauty of the moment that are at the heart of the tea ceremony.

Spirituality plays a central role in Japanese culture, and Bizen pottery has found a firm place in this area as well. It is often used in Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, where it serves as vessels for flowers, incense, or offerings.

Bizen pottery is also highly valued in Zen Buddhist practices, as its simplicity and naturalness reflect the principles of Zen. The use of Bizen vases for ikebana (the art of flower arranging) in temples underlines the connection between art, spirituality, and nature.

In Shintoism, Bizen pottery is often used as a vessel for sake offerings or water. The natural properties of the clay and the robustness of the pottery make it ideal for use in rituals that emphasize purity and simplicity.

In addition to its spiritual and cultural significance, Bizen pottery also has a long history in Japanese cuisine and everyday life. Their durability and functionality make them ideal for everyday use, while their aesthetics enrich everyday life.

Bizen pottery is often used for plates, bowls and pitchers. Their rustic appearance fits perfectly with traditional Japanese cuisine, where the presentation of food is as important as its taste. The porous surface of the pottery retains moisture, which is particularly beneficial when storing water or sake.

But Bizen pottery is also a popular material for sake pitchers and cups. The thickness of the pottery keeps the temperature of the sake constant, whether hot or cold. At the same time, the rough texture provides a tactile experience that intensifies enjoyment.

Historically, Bizen pottery was a symbol of wealth and status. In the Edo period (1603–1868), it was prized by samurai and wealthy merchants who decorated their living spaces with exquisite ceramic pieces. The samurai class valued the robustness and simplicity of Bizen pottery, as they associated these qualities with their own values ??of strength and modesty. Many samurai used Bizen pottery for tea ceremonies or as decorative items in their residences. But wealthy merchants and nobles also viewed Bizen pottery as collector’s items and as a sign of their cultural awareness. Particularly elaborately designed pieces, produced in lengthy firing processes, were considered particularly prestigious.

The cultural significance of Bizen pottery has evolved in modern times. Today, it is not only valued as a traditional craft, but also interpreted as an expression of contemporary art. Modern artists use the techniques and materials of Bizen pottery to create innovative designs that combine traditional and modern aesthetics. These works are recognized not only in Japan but also internationally and can be found in galleries and museums around the world. As a result, Bizen pottery is sought after by collectors worldwide. Its connection to Japanese culture, its unique aesthetic and the fact that each piece is one of a kind make it a prized possession.

Much more than just a craft product, Bizen pottery is a cultural symbol deeply embedded in Japanese history and philosophy. From spiritual practice to the tea ceremony to everyday use and modern art, it has inspired and enriched generations of people.

Famous Masters of Bizen Ceramics

Over the centuries, numerous masters have carried on the tradition of Bizen ceramics. Kaneshige Toyo, who was named a “Living National Treasure” of Japan in 1956, deserves special mention. His work played a key role in establishing Bizen ceramics in the modern art world. The art of Bizen ceramics has been shaped by the work of exceptional masters for generations. These artists, known as “Bizen-Toji”, have helped make Bizen ceramics what it is today: one of Japan’s most highly valued ceramic forms, through their craftsmanship, innovative techniques and dedication to tradition. Some of these masters have not only shaped Japanese ceramic history with their works, but have also achieved international recognition.

Kaneshige Toyo

Kaneshige Toyo (1896–1967) is arguably the most famous name in the history of 20th century Bizen pottery. He was designated a “Living National Treasure” (Ningen Kokuho) by the Japanese government in 1956 and is considered a key figure in the revival of traditional Bizen pottery techniques after World War II.

Kaneshige devoted his life to rediscovering and perfecting techniques lost in the Edo period. His works focused on the original methods of firing and the aesthetics of the Muromachi and Momoyama periods. Although he was a champion of tradition, Kaneshige experimented with new designs and forms that combined modern elements with classical techniques. Kaneshige’s works are known for their simple elegance and subtle use of hidasuki (fire-cord) patterns. His tea bowls and vases are particularly prized.

Fujiwara Kei

Fujiwara Kei (1899-1983) is another outstanding figure in the history of Bizen ceramics. He too was honored as a Living National Treasure in 1970. Fujiwara placed great emphasis on combining craftsmanship with personal expression. Unlike other masters who were strongly influenced by traditional forms, Fujiwara was known for bringing a personal, emotional touch to his works.

He played a crucial role in training and inspiring young artists who continued the tradition of Bizen ceramics. His works are characterized by a rougher texture and a deeper connection to natural aesthetics. His tea bowls and water jars, which often have a powerful, rustic appearance, are particularly valued.

Yokoyama Naoki

Yokoyama Naoki (1941-2017) was known for his innovative approach to Bizen ceramics. Although deeply rooted in tradition, he strove to find new forms of expression within the medium. Yokoyama experimented with new firing techniques and forms that pushed the boundaries of classic Bizen ceramics. His works were exhibited not only in Japan but also internationally, making Bizen ceramics known worldwide. His ceramics are often large-scale and have bold, irregular shapes. He played with yohen effects (kiln changes) to achieve unusual colors and textures.

Kawabata Fumio

Kawabata Fumio (1937-2018) is known for his meticulous attention to detail and his ability to bring out the subtlest nuances in his works. Kawabata was a master at enhancing the natural beauty of the clay through precise control of the firing process. Despite his attention to detail, he remained true to classic Bizen pottery, creating works that were both traditional and timeless. His pieces show a remarkable balance between simplicity and rich detail. The delicate Hidasuki patterns and harmonious shapes of his tea bowls and jugs are particularly striking.

Kimura Boku

Kimura Boku (born 1975) belongs to the younger generation of Bizen ceramicists and brings a breath of fresh air to the traditional art form. Kimura combines classic Bizen techniques with contemporary forms and concepts to make the pottery relevant to a new generation of art lovers. He places great emphasis on sustainable practices, such as the use of local materials and environmentally friendly firing methods. His works are often experimental and break with the conventions of traditional Bizen pottery. Nevertheless, the essence of the Bizen tradition remains in the materials and techniques used.

The masters of Bizen ceramics, from Kaneshige Toyo to modern artists such as Kimura Boku, have preserved and developed the tradition of this ceramic form through their unique vision and craftsmanship. Each master brings his own signature and personal contribution, ensuring that Bizen pottery remains a living and dynamic art form that both honors the past and shapes the future.

My conclusion: challenges and revival

The Industrial Revolution and World War II led to a decline in demand for traditional ceramics. But with dedicated artists and the support of the Japanese government, Bizen ceramics were revitalized. Today, it is appreciated not only in Japan, but worldwide. Bizen ceramics combine tradition, art and functionality in a unique way. Its simple elegance and the unpredictable patterns of fire make it a fascinating testament to Japanese craftsmanship.

One of Japan’s oldest and most respected ceramic traditions, Bizen ceramics is a living testament to human creativity, patience and a deep connection to nature. Despite its rich cultural heritage, it too faces challenges that present both threats and opportunities in an ever-changing world.

The Industrial Revolution and technological advances of the 20th century fundamentally changed the demand for handmade ceramics. Machine-made products offer inexpensive alternatives that often appear more functional and are less time-consuming to produce.

Making Bizen pottery requires a deep understanding of material, technique, and firing processes—knowledge that has been passed down through generations. The number of skilled ceramicists who have mastered the traditional techniques is dwindling. Many masters face the challenge of passing on their knowledge to a new generation in a timely manner. The laborious production and long firing times pose a hindrance for many potters, especially in a fast-paced society.

Despite the challenges mentioned, there is a notable movement aimed at preserving and revitalizing Bizen pottery. These efforts combine respect for tradition with innovative approaches to make the art form relevant for future generations. Modern ceramicists are bringing a breath of fresh air to Bizen art by combining traditional techniques with contemporary design. Artists such as Kimura Boku and Yokoyama Naoki are experimenting with unconventional designs to make Bizen pottery accessible to a wider audience. Through exhibitions in galleries and museums worldwide, Bizen pottery is finding new admirers and markets outside Japan.

The designation of major ceramicists such as Kaneshige Toyo and Fujiwara Kei as Living National Treasures has helped to increase public awareness of Bizen pottery. The Japanese government supports programs and scholarships to encourage the training of new potters and the preservation of traditional techniques. The Okayama region has become a major destination for cultural tourism, further increasing interest in Bizen pottery.

The challenges facing Bizen pottery are significant, but efforts to revive it show that it can endure in the modern world. The combination of tradition and innovation, coupled with a growing global awareness of the importance of handicrafts, offers hope for the future. Bizen pottery is not just a relic of the past, but a living example of man’s ability to create beauty through creativity and dedication – an art form that sees its challenges as an opportunity for growth and transformation.